Scientists got it wrong on gravitational waves. So what? It was announced in headlines worldwide as one of the biggest scientific discoveries for decades, sure to garner Nobel prizes.

But now it looks likely that the alleged evidence of both gravitational waves and ultra-fast expansion of the universe in the big bang (called inflation) has literally turned to dust. Last March, a team using a telescope called Bicep2 at the South Pole claimed to have read the signatures of these two elusive phenomena in the twisting patterns of the cosmic microwave background radiation: the afterglow of the big bang. But this week, results from an international consortium using a space telescope called Planck show that Bicep2’s data is likely to have come not from the microwave background but from dust scattered through our own galaxy. Some will regard this as a huge embarrassment, not only for the Bicep2 team but for science itself.

But there’s no shame here. ‘Gravitational waves’ may have been space dust. Scientists who caused a global sensation when they announced the discovery of gravitational waves may have been fooled by bits of dust floating about in space.

Researchers at Harvard University called a press conference in March to reveal that they had spotted the cosmic signature of ripples in space left over from the spectacular expansion of the early universe. The dramatic claim was hailed as one of the most important scientific discoveries of the century and promised a new era of physics.

But the findings, which some experts doubted from the off, have received a serious blow from researchers with the European Space Agency’s Planck mission, who found that galactic dust could fully explain the observation. “It’s certainly possible that the results can be explained purely by dust,” said Jo Dunkley, professor of astrophysics and a member of the Planck team at Oxford University. But light can be twisted by other means. “It’s typical messy science,” said Efstathiou. Gravitational waves turn to dust after claims of flawed analysis. It was hailed as one of the most important scientific discoveries of the century, the birth of a new era in physics and a shoo-in for a Nobel prize.

The claim from Harvard University that it had discovered gravitational waves – and thereby evidence for the theory of cosmic inflation and the existence of a multiverse – caused a worldwide sensation in March. But the celebrations are now looking decidedly premature. Rather than securing a trip to Stockholm to receive a Nobel medal, the Harvard team may have detected nothing more than space dust.

Writing in the journal Nature on Wednesday, Paul Steinhardt, director of the Centre for Theoretical Physics at Princeton University, argues that the Harvard team made an unfortunate blunder in its calculations. "Serious flaws in the analysis have been revealed that transform the sure detection into no detection," he writes. What are gravitational waves? What are gravitational waves?

Gravitational waves are ripples that carry energy across the universe. They were predicted to exist by Albert Einstein in 1916 as a consequence of his General Theory of Relativity. Although there is strong circumstantial evidence for their existence, gravitational waves have not been directly detected before. This is because they are minuscule – a million times smaller than an atom. First glimpse of big bang ripples from universe's birth - physics-math - 17 March 2014. Read full article Continue reading page |1|2 (Image: Steffen Richter/Harvard) Waves in the very fabric of the cosmos are allowing us to peer further back in time than anyone thought possible, showing us what was happening in the first slivers of a second after the big bang.

If confirmed, the discovery of these primordial waves will have rippling effects throughout science. It backs up key predictions for how the universe began and operates, and offers a glimmer of hope for tying together two foundational theories of modern physics. Primordial gravitational wave discovery heralds 'whole new era' in physics. Scientists have heralded a "whole new era" in physics with the detection of "primordial gravitational waves" – the first tremors of the big bang.

The minuscule ripples in space-time are the last prediction of Albert Einstein's 1916 general theory of relativity to be verified. Until now, there has only been circumstantial evidence of their existence. The discovery also provides a deep connection between general relativity and quantum mechanics, another central pillar of physics. "This is a genuine breakthrough," says Andrew Pontzen, a cosmologist from University College London who was not involved in the work. "It represents a whole new era in cosmology and physics as well. " The detection, which has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal, was announced on Monday at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and comes from the Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarization 2 (Bicep2) experiment – a telescope at the South Pole.

Landmark Discovery: New Results Provide Direct Evidence for Cosmic Inflation. Want to stay on top of all the space news?

Follow @universetoday on Twitter The BICEP telescope located at the south pole. Image Credit: Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. George Smoot: We mapped the embryonic universe. Gravitational waves: have US scientists heard echoes of the big bang? There is intense speculation among cosmologists that a US team is on the verge of confirming they have detected "primordial gravitational waves" – an echo of the big bang in which the universe came into existence 14bn years ago.

Rumours have been rife in the physics community about an announcement due on Monday from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. If there is evidence for gravitational waves, it would be a landmark discovery that would change the face of cosmology and particle physics. Gravitational waves are the last untested prediction of Albert Einstein's General Theory of Relativity. They are minuscule ripples in the fabric of the universe that carry energy across space, somewhat similar to waves crossing an ocean.

Convincing evidence of their discovery would almost certainly lead to a Nobel prize. "If they do announce primordial gravitational waves on Monday, I will take a huge amount of convincing," said Hiranya Peiris, a cosmologist from University College London. Rumors Flying Nearly as Fast as Their Subject: Have Gravitational Waves Been Detected? Want to stay on top of all the space news?

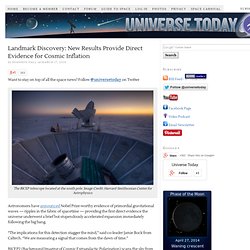

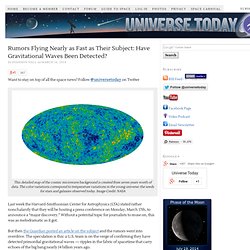

Follow @universetoday on Twitter This detailed map of the cosmic microwave background is created from seven years worth of data. The color variations correspond to temperature variations in the young universe: the seeds for stars and galaxies observed today. Image Credit: NASA Last week the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) stated rather nonchalantly that they will be hosting a press conference on Monday, March 17th, to announce a “major discovery.” Detection of primordial gravitational waves announced.

When the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics announced a press conference for a "Major Discovery" (capital letters in the original e-mail) involving an unspecified experiment, rumors began to fly immediately.

By Friday afternoon, the rumors had coalesced around one particular observatory: the BICEP microwave telescope located at the South Pole. Stephen Hawking claims victory in gravitational wave bet. Stephen Hawking has claimed victory in a bet with a fellow scientist over the discovery of primordial gravitational waves, ripples in the structure of space-time from the birth of the universe. The Cambridge cosmologist bet Neil Turok, director of the Perimeter Institute in Canada, that gravitational waves from the first fleeting moments after the big bang would be detected. Speaking on BBC Radio 4's Today programme, Hawking said the discovery of gravitational waves, announced on Monday by researchers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics, disproves Turok's theory that the universe cycles endlessly from one big bang to another.