Mathematical constant A mathematical constant is a special number, usually a real number, that is "significantly interesting in some way".[1] Constants arise in many different areas of mathematics, with constants such as e and π occurring in such diverse contexts as geometry, number theory and calculus. What it means for a constant to arise "naturally", and what makes a constant "interesting", is ultimately a matter of taste, and some mathematical constants are notable more for historical reasons than for their intrinsic mathematical interest. The more popular constants have been studied throughout the ages and computed to many decimal places. All mathematical constants are definable numbers and usually are also computable numbers (Chaitin's constant being a significant exception). Common mathematical constants[edit] These are constants which one is likely to encounter during pre-college education in many countries. Archimedes' constant π[edit] The circumference of a circle with diameter 1 is π. Besides

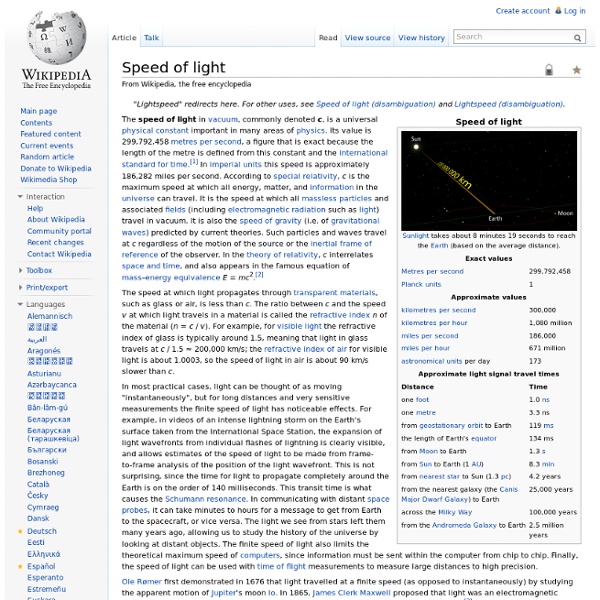

Physical constant There are many physical constants in science, some of the most widely recognized being the speed of light in vacuum c, the gravitational constant G, Planck's constant h, the electric constant ε0, and the elementary charge e. Physical constants can take many dimensional forms: the speed of light signifies a maximum speed limit of the Universe and is expressed dimensionally as length divided by time; while the fine-structure constant α, which characterizes the strength of the electromagnetic interaction, is dimensionless. Dimensional and dimensionless physical constants[edit] Whereas the physical quantity indicated by any physical constant does not depend on the unit system used to express the quantity, the numerical values of dimensional physical constants do depend on the unit used. However, the term fundamental physical constant is also used in other ways. The fine-structure constant α is probably the best known dimensionless fundamental physical constant. Anthropic principle[edit]

Corpuscular theory of light In optics, the corpuscular theory of light, arguably set forward by Descartes (1637) states that light is made up of small discrete particles called "corpuscles" (little particles) which travel in a straight line with a finite velocity and possess impetus. This was based on an alternate description of atomism of the time period. This theory cannot explain refraction, diffraction, interference and polarization. Mechanical philosophy[edit] Pierre Gassendi's atomist matter theory[edit] The core of Gassendi's philosophy is his atomist matter theory. God existsGod created a finite number of indivisible and moving atomsGod has a continuing divine relationship to creation (of matter)Free willA human soul exists.[1] He thought that atoms move in an empty space, classically known as the void, which contradicts the Aristotelian view that the universe is fully made of matter. Corpuscularian theories[edit] Corpuscularian theory to describe light[edit] Sir Isaac Newton[edit] See also[edit]

Kinetic energy Energy of a moving physical body In classical mechanics, the kinetic energy of a non-rotating object of mass m traveling at a speed v is . In relativistic mechanics, this is a good approximation only when v is much less than the speed of light. The standard unit of kinetic energy is the joule, while the English unit of kinetic energy is the foot-pound. History and etymology The adjective kinetic has its roots in the Greek word κίνησις kinesis, meaning "motion". The principle in classical mechanics that E ∝ mv2 was first developed by Gottfried Leibniz and Johann Bernoulli, who described kinetic energy as the living force, vis viva. Overview Energy occurs in many forms, including chemical energy, thermal energy, electromagnetic radiation, gravitational energy, electric energy, elastic energy, nuclear energy, and rest energy. The kinetic energy in the moving cyclist and the bicycle can be converted to other forms. Kinetic energy can be passed from one object to another. Newtonian kinetic energy

Principles of Philosophy Principia Philosophiæ, 1685 The illustration of movement of objects from the Principles Principles of Philosophy (Latin: Principia Philosophiæ) is a book by René Descartes. In essence it is a synthesis of the Discourse on Method and Meditations on First Philosophy[1] It was written in Latin, published in 1644 and dedicated to Elisabeth of Bohemia, with whom Descartes had a long-standing friendship. A French version (Les Principes de la Philosophie) followed in 1647. It set forth the principles of nature—the Laws of Physics—as Descartes viewed them. Preface to the French edition[edit] Descartes asked Abbot Claude Picot to translate his Latin Principia Philosophiæ into French. Concept of philosophy. The degrees of knowledge. Higher wisdom. Doubt and certainty. Meditations on first philosophy. The tree of philosophy. Copies and prints[edit] René Descartes' Principia Philosophiæ. Editions[edit] Descartes, René (1983) [1644, with additional material from the French translation of 1647].

Marin Mersenne Life[edit] For four years, Mersenne devoted himself entirely to philosophic and theological writing, and published Quaestiones celeberrimae in Genesim (1623); L'Impieté des déistes (1624); La Vérité des sciences (Truth of the Sciences Against the Sceptics, 1624). It is sometimes incorrectly stated that he was a Jesuit. He was educated by Jesuits, but he never joined the Society of Jesus. He taught theology and philosophy at Nevers and Paris. In 1635 he set up the informal Académie Parisienne (Academia Parisiensis), which had nearly 140 correspondents, including astronomers and philosophers as well as mathematicians, and was the precursor of the Académie des sciences established by Jean-Baptiste Colbert in 1666. In 1635 Mersenne met with Tommaso Campanella but concluded that he could "teach nothing in the sciences ... but still he has a good memory and a fertile imagination." He died September 1 through complications arising from a lung abscess. Works[edit] Other[edit] Music[edit]

Galileo Galilei Italian physicist and astronomer (1564–1642) Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( GAL-il-AY-oh GAL-il-AY, GAL-il-EE-oh -, Italian: [ɡaliˈlɛːo ɡaliˈlɛi]) or simply Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. He was born in the city of Pisa, then part of the Duchy of Florence.[4] Galileo has been called the father of observational astronomy,[5] modern-era classical physics,[6] the scientific method,[7] and modern science.[8] Galileo's championing of Copernican heliocentrism (Earth rotating daily and revolving around the Sun) was met with opposition from within the Catholic Church and from some astronomers. Galileo later defended his views in Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632), which appeared to attack Pope Urban VIII and thus alienated both the Pope and the Jesuits, who had both supported Galileo up until this point. Name[edit] Moon[edit]

What Are Redshift and Blueshift? Redshift and blueshift describe the change in the frequency of a light wave depending on whether an object is moving toward or away from us. When an object is moving away from us, the light from the object is known as redshift, and when an object is moving towards us, the light from the object is known as blueshift. Astronomers use redshift and blueshift to deduce how far an object is away from Earth, the concept is key to charting the universe's expansion. Related: What is a light-year? To understand redshift and blueshift, first, you need to remember that visible light is a spectrum of color each with a different wavelength. According to NASA, violet has the shortest wavelength at around 380 nanometers, and red has the longest at around 700 nanometers. Redshift, blueshift and the Doppler effect We've all heard how a siren changes as a police car rushes past, with a high pitch siren upon approach, shifting to a lower pitch as the vehicle speeds away. Jason Steffens Three types of redshift

Roman Inquisition The Roman Inquisition, formally the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition, was a system of tribunals developed by the Holy See of the Roman Catholic Church, during the second half of the 16th century, responsible for prosecuting individuals accused of a wide array of crimes relating to religious doctrine or alternate religious doctrine or alternate religious beliefs. In the period after the Medieval Inquisition, it was one of three different manifestations of the wider Catholic Inquisition along with the Spanish Inquisition and Portuguese Inquisition. Objectives[edit] Function[edit] History[edit] While the Roman Inquisition was originally designed to combat the spread of Protestantism in Italy, the institution outlived that original purpose and the system of tribunals lasted until the mid 18th century, when pre-unification Italian states began to suppress the local inquisitions, effectively eliminating the power of the church to prosecute heretical crimes.