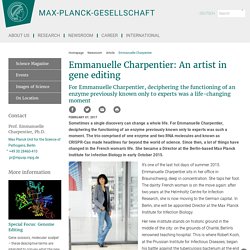

Portrait d'Emmanuelle Charpentier, Prix Nobel de chimie 2020. Emmanuelle Charpentier. For Emmanuelle Charpentier, deciphering the functioning of an enzyme previously known only to experts was a life-changing moment Sometimes a single discovery can change a whole life.

For Emmanuelle Charpentier, deciphering the functioning of an enzyme previously known only to experts was such a moment. The trio comprised of one enzyme and two RNA molecules and known as CRISPR-Cas made headlines far beyond the world of science. Since then, a lot of things have changed in the French woman’s life. She became a Director at the Berlin-based Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology in early October 2015. Not So Elementary, Watson. Franklin was not a man-hating harpy but neither was she an easy woman to know or to like.

She was stiff and mercurial; when she felt denigrated or unappreciated, she turned ''abrupt and peremptory,'' a colleague said, with a sharp, caustic ''spikiness'' (Wilkins's characterization) that turned people against her. But when she was happy, off on one of her many hiking trips through Europe, giving lavish dinner parties in her flat or visiting with friends, Franklin could be clever, sparkling, beautiful, provocative -- in short, a sheer delight.

The more difficult moments were many, however, no doubt partly caused by the difficulty women had being taken seriously in science, especially in Franklin's field, physical chemistry. Rosalind Franklin was so much more than the ‘wronged heroine’ of DNA. At the centre of Rosalind Franklin’s tombstone in London’s Willesden Jewish Cemetery is the word “scientist”.

This is followed by the inscription, “Her research and discoveries on viruses remain of lasting benefit to mankind.” As one of the twentieth century’s pre-eminent scientists, Franklin’s work has benefited all of humanity. The one-hundredth anniversary of her birth this month is prompting much reflection on her career and research contributions, not least Franklin’s catalytic role in unravelling the structure of DNA. She is best known for an X-ray diffraction image that she and her graduate student Raymond Gosling published in 19531, which was key to the determination of the DNA double helix. But Franklin’s remarkable work on DNA amounts to a fraction of her record and legacy. Sexism pushed Rosalind Franklin toward the scientific sidelines during her short life, but her work still shines on her 100th birthday.

What do coal, viruses and DNA have in common?

The structures of each – the predominant power source of the early 20th century, one of the most remarkable forms of life on Earth and the master molecule of heredity – were all elucidated by one person. Her name was Rosalind Franklin, and the story of her triumph over sexism and rise to scientific greatness is made even more remarkable by the fact that she lived only 37 years. In Franklin’s day, sexism ran rampant in science. Her own father, judging science no career for a woman, actively discouraged her aspirations. Her doctoral supervisor at Cambridge, eventual Nobel Laureate Ronald G.W. Rosalind Franklin: Mars rover named after DNA pioneer. Image copyright Getty Images/ESA The UK-assembled rover that will be sent to Mars in 2020 will bear the name of DNA pioneer Rosalind Franklin.

The honour follows a public call for suggestions that drew nearly 36,000 responses from right across Europe. Astronaut Tim Peake unveiled the name at the Airbus factory in Stevenage where the robot is being put together. The six-wheeled vehicle will be equipped with instruments and a drill to search for evidence of past or present life on the Red Planet. Image copyright Max Alexander / AIRBUS Giving the rover a name associated with a molecule fundamental to biology seems therefore to be wholly appropriate.

Rosalind Franklin played an integral role in the discovery of the structure of deoxyribonucleic acid. It was her X-ray images that allowed James Watson and Francis Crick to decipher its double-helix shape. Franklin's early death from ovarian cancer in 1958, aged just 37, meant she never received the recognition given to her male peers. Rosalind Franklin centenary: 'She would have been totally amazed' Image copyright The Franklin family Scientist Rosalind Franklin would have been "totally amazed" that 100 years after her birth she is being commemorated, according to her sister.

She is best known for her pioneering work which guided Francis Crick and James Watson to unlock DNA's secrets. But far more of her short career was spent unravelling the molecular structures of coal and viruses. Jenifer Glynn, 90, said she would have been pleased if her career "encourages girls into science". Rosalind Franklin was one of five siblings who grew up in London. She secured a place at the University of Cambridge to study chemistry in 1938, and charted her life there through weekly letters home.

Mrs Glynn, who lives in Cambridge, said: "She always wanted the proof of things - while she was a good all-rounder at school, it was clear from the start she was going to be a scientist. "There was no feeling in the family or at the university that it was odd for a woman to study science. " Image copyright SPL. Rosalind Franklin, pionnière de l'ADN. Le 18 octobre 1962, le prix Nobel de médecine est attribué à trois hommes, James Watson, Francis Crick et Maurice Wilkins, pour la découverte de la structure en double hélice de l’ADN.