Autistic Hoya: Ableism/Language. Last updated 4 April 2016.

Note that some of the words on this page are actually slurs but many of the words and phrases on this page are not considered slurs. They are simply considered ableist (the way that referring to a woman as emotionally fragile is sexist, but not a slur). You're not automatically a bad or evil person/activist if you have used random language on here, but if you have the cognitive/language privilege to adjust your language, it's definitely worthwhile.For my most recent perspective on linguistic ableism and the reason that this page exists, see this post: Violence in Language: Circling Back to Linguistic Ableism.

Ableism is not a list of bad words. Language is *one* tool of an oppressive system. Ableism is to blame. Trigger warning: murder, lots and lots of ableism.

I saw a girl post an apology for the fact that she has autism, that she will never be what her parents want her to be. I responded to her with the usual message of it's ok, it really is, autism isn't the end of the world. Intelligence is ableist, but not for the reason you think. It’s not ableist to acknowledge that people have varying ability levels.

I mean obviously come on that’s like, one of the most basic points of disability theory. Intelligence is ableist because it isn’t actually a thing. It’s a bunch of things, and often they aren’t correlated at all (See for example specific learning disabilities; like I’m completely unable to remember things in the short term and get distracted all the time and forget what I was doing but as soon as something is in my long term memory it is staying there forever.) Like the best way to put it seems to be to realize it’s not really one specific thing. It is probably worth breaking the idea down into its component parts here, because really my ability to grasp complex concepts quickly and my tendency to become completely lost if a person uses weird organization or is at all poetic are very different things, and they’d both be considered intelligence or lack thereof.

Here's What Neurodiversity Is – And What It Means For Feminism. With the rise in autism and other developmental and learning disability diagnoses over the last few decades, conversations around neurodiversity – which is the idea that neurological differences like autism and ADHD are the result of normal, natural variation in the human genome, not the result of disease or injury.

It’s a fairly new concept that’s gaining traction in the disability rights movement and is coming into the spotlight like never before. And mainstream media outlets like Wired, The Atlantic, and Slate Magazine have been picking up on the budding social justice movement that’s attached to it. Steve Silberman’s new book Neurotribes, about the history of autism, is topping the bestseller charts. You might wonder what disability and neurodiversity have to do with feminism. We tend to fall into the trap of thinking disability isn’t a feminist or social justice issue, because disability has been so entwined with medicine and the medical field for so long. 1. What is the social model of disability? The social model of disability says that disability is caused by the way society is organised, rather than by a person’s impairment or difference.

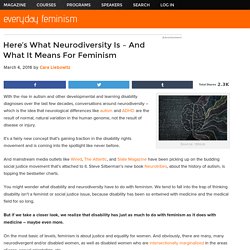

It looks at ways of removing barriers that restrict life choices for disabled people. When barriers are removed, disabled people can be independent and equal in society, with choice and control over their own lives. Disabled people developed the social model of disability because the traditional medical model did not explain their personal experience of disability or help to develop more inclusive ways of living. An impairment is defined as long-term limitation of a person’s physical, mental or sensory function. Changing attitudes to disabled people. Olivia Wilde Plays a Girl With Down Syndrome in Eye-Opening Film. Editor's Pick Actress Olivia Wilde appears in the latest moving film by Saatchi & Saatchi for CoorDown, Italy's national organization for people with Down Syndrome.

Previous efforts by Saatchi' s Milan office for the charity have won awards including 18 Cannes Lions, and this time the agency's New York office worked on the spot, which is narrated by a 19-year-old college student with Down Syndrome, Anna Rose Rubright. In this film, Wilde plays AnnaRose as she sees herself -- an ordinary girl, out with her family, laughing, crying, running and dancing. It's only at the end we see the real Anna Rose, and she asks "How do you see me? " The spot, directed by Reed Morano at Pulse Films, highlights World Down Syndrome Day on March 21. This Comic Reveals the Hidden Struggles of Living with Invisible Disabilities.

Originally published on Empathize This and republished here with their permission.

Editor’s Note: The text below the comic was submitted by a reader to the original publisher. The author uses the term “female-bodied,” which doesn’t reflect our preferred language, as the term implies that a female body is made up of particular parts. The unspoken struggles and stigma of living with invisible disabilities come out from the shadows. We hope it makes a difference for something that’s far too often misunderstood. With Love, The Editors at Everyday Feminism I am 31 and female-bodied. On bad days, they all collide – I struggle not to feel angry (or at least not to show it), I feel like I’m in a fog, and my joints are so stiff I can’t get up without someone picking me up off the ground. No one wants to believe that a woman who looks like she’s barely old enough for college – just a girl, just a girl – has chronic and recurring pain. Needless to say, it’s hard to hold down a job.

This Is Why It Hurts When You Say These Things to People with Chronic Pain (And Some Ideas on How to Support Instead) Panel 1 A woman (Alli) is speaking directly to the camera, holding an x-ray film of a torso with the word “ow” written in place of one of the vertebrae.

Alli: Hi, I’m Alli, your cartoonist, and I have a benign tumor in my spine that makes me hurt pretty much all the time. This Insider's View of Schizophrenia Proves That Neurotypical Privilege Exists. This Comic Nails What It's Like to Live With Mental Illness – And It's Not Like Most People Think. Panel 1 (A picture of a person wearing eyeglasses looking to the side with a wide eyed, sad expression on the face.

Both hands are raised up. The head and one side to the level of just below the shoulder are surrounded by the word AAAAAAAAHHHHH!!! In an arc. I'm Schizophrenic, Not a 'Person with Schizophrenia' — So Please Stop Correcting Me. Panel 1 Text: My Language is My Identity – Christine Deneweth Panel 2 (Crass talking and smiling.

She has short curly hair, glasses and is wearing a T-shirt.) Crass: Hi. Mouth Magazine: Dedicated to disability rights & discrimination issues.