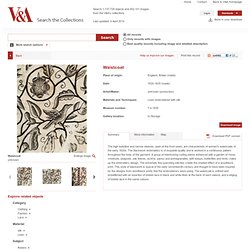

Pair of sleeve panels. Handkerchief. Jacket. The high waistline and narrow sleeves, open at the front seam, are characteristic of women's waistcoats of the early 1620s.

The blackwork embroidery is of exquisite quality and is worked in a continuous pattern throughout the body of the garment. A group of interlocking curling stems enhanced with a garden of roses, rosebuds, peapods, oak leaves, acorns, pansy and pomegranates, with wasps, butterflies and birds, make up the embroidery design. The extremely fine speckling stitches create the shaded effect of a woodblock print. This style of blackwork is typical of the early seventeenth-century and thought to have been inspired by the designs from woodblock prints that the embroiderers were using. The waistcoat is unlined and embellished with an insertion of bobbin lace in black and white linen at the back of each sleeve, and a edging of bobbin lace in the same colours.

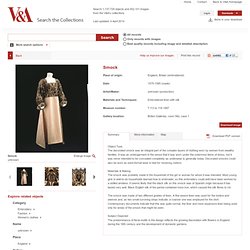

Physical description Place of Origin England, Britain (made) Date 1620-1625 (made) Artist/maker unknown (production) Dimensions. Smock. Object Type The decorated smock was an integral part of the complex layers of clothing worn by women from wealthy families.

It was an undergarment in the sense that it was worn under the outermost items of dress, but it was never intended to be concealed completely as underwear is generally today. Decorated smocks could also be worn as semi-formal wear in bed for receiving visitors. Materials & Making The smock was probably made in the household of the girl or woman for whom it was intended. Most young girls in well-to-do households learned how to embroider, so this embroidery could well have been worked by a skilled amateur. It seems likely that the black silk on this smock was of Spanish origin because it has lasted very well. The smock was made of two different grades of linen. Subject Depicted The predominance of floral motifs in the design reflects the growing fascination with flowers in England during the 16th century and the development of domestic gardens. Physical description. English Embroidery of the Late Tudor and Stuart Eras. The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw a flowering of the art of embroidery for secular use, particularly in England.

During the Middle Ages, English artisans were famed throughout Europe for their embroidered church vestments. However, from the time that King Henry VIII severed relations with the Catholic church in 1534 and established the Church of England, the need for elaborately decorated religious vestments and furnishings for worship diminished greatly.

But by the late sixteenth century, the taste for rich clothing and domestic decorations increased and a larger portion of society could afford to buy or make these luxury items during the relatively peaceful and prosperous late years of Elizabeth I's reign. A surprisingly large number of fragile embroidered objects have survived in public and private collections. A variety of contemporary concerns and opinions about nature, faith, family relationships, and the monarchy are reflected in the embroidery designs (39.13.7). Google Image Result for. Woman's Coif 16th century-English-Museaum of Fine Arts,Boston 16th century man's nightcap Victoria & Albert Museum,London 16th century Coif,English 16th century Forehead Cloths 17th century Coif,Victoria & Albert Museum,London 1600-1630 Coif,The Burrell Collection,Glasgow Museum 16th century Forehead Cloth 16th century Coif, Victoria & Albert Museum,London Linen caps called coifs were worn under hoods or hats.

The term "coif" referred to a man's close fitting linen cap which resembled a baby's bonnet. The coifs were sometimes worn with a forehead cloth, which was known as a "crosscloth", and many matching sets were decorated with similar embroidery. Introduction to English embroidery. Detail from the Syon Cope, early 14th century.

Museum no. 83-1864 Medieval embroidery During the middle ages embroidery was a popular way of decorating luxury textiles. Blackwork fragment. Stomacher. Pillow cover. Smock.