Le Devoir. Bloody Sunday - Selma, Alabama. Lyndon B. Johnson, "We Shall Overcome" (15 March 1965) Garth E.

Pauley President Lyndon Johnson's voting rights speech of March 15, 1965, is considered a landmark of oratory. It is reprinted or excerpted in nearly every anthology that chronicles the "great moments" or "great issues" of American history. Leading scholars of American oratory have ranked Johnson's speech as one of the top ten American speeches of the twentieth century.[1] Even so, it is not unreasonable to ask, "Is the speech really that outstanding? " Johnson hardly can be counted among the nation's great orators. While it is true that Johnson was not a gifted public speaker in general and that the protests elicited support for voting rights legislation, the voting rights speech is indeed an exceptional instance of political oratory. Speaker Born and raised in the Texas Hill Country during the early twentieth century, Lyndon Johnson's childhood experiences did not predispose him to become an advocate of racial justice.

Interpretation Garth E. . [1] Stephen E. . [5] Robert A. Un film pour commémorer la marche de Selma, 50 ans après. ExpandMap.png (PNG Image, 1188 × 618 pixels) - Scaled (86%) Les États-Unis hantés par cinquante ans d'émeutes raciales. Des émeutes intervenant après des altercations, souvent mortelles, entre policiers et membres de la communauté noire : depuis la fin de la ségrégation, le même scénario se répète à intervalles réguliers.

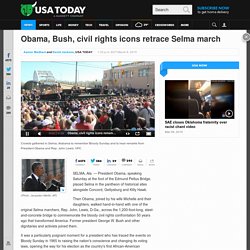

Six ans après son élection, Barack Obama est rattrapé par la question noire. Un problème qui hante l'Amérique depuis la fin de la ségrégation il y a cinquante ans. Des émeutes du ghetto de Watts en 1965 à la toute récente affaire de Ferguson, c'est à chaque fois le même scénario qui se profile: à l'origine, une altercation policière plus ou moins meurtrière qui dégénère en révolte de la communauté noire. • 1965, Los Angeles: «Burn, baby burn!» Malgré la mise en place du Civil Rights Act en 1964 qui met fin officiellement à la ségrégation raciale, les discriminations continuent et la situation est explosive à Los Angeles, où une forte communauté noire est installée dans le quartier de Watts. . • 1967: «A long hot summer» L'été de 1967 est chaud aux Etats-Unis. . • 1980: les émeutes de Miami. Selma to Montgomery March. Obama, Bush, civil rights icons retrace Selma march. Crowds gathered in Selma, Alabama to remember Bloody Sunday and to hear remarks from President Obama and Rep.

John Lewis. VPC SELMA, Ala. — President Obama, speaking Saturday at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, placed Selma in the pantheon of historical sites alongside Concord, Gettysburg and Kitty Hawk. Then Obama, joined by his wife Michelle and their daughters, walked hand-in-hand with one of the original Selma marchers, Rep. John, Lewis, D-Ga., across the 1,200-foot-long, steel-and-concrete bridge to commemorate the bloody civil rights confrontation 50 years ago that transformed America. It was a particularly poignant moment for a president who has traced the events on Bloody Sunday in 1965 to raising the nation's conscience and changing its voting laws, opening the way for his election as the country's first African-American president.

Selma to Montgomery March (1965) On 25 March 1965, Martin Luther King led thousands of nonviolent demonstrators to the steps of the capitol in Montgomery, Alabama, after a 5-day, 54-mile march from Selma, Alabama, where local African Americans, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) had been campaigning for voting rights.

King told the assembled crowd: ‘‘There never was a moment in American history more honorable and more inspiring than the pilgrimage of clergymen and laymen of every race and faith pouring into Selma to face danger at the side of its embattled Negroes’’ (King, ‘‘Address at the Conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery March,’’ 121). Bloody Sunday, Selma, Alabama, (March 7, 1965) Alabama State Troopers Attack John Lewis at the Edmund Pettis Bridge "Image Ownership: Public Domain" Between 1961 and 1964, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had led a voting registration campaign in Selma, the seat of Dallas County, Alabama, a small town with a record of consistent resistance to black voting.

When SNCC’s efforts were frustrated by stiff resistance from the county law enforcement officials, Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) were persuaded by local activists to make Selma’s intransigence to black voting a national concern. SCLC also hoped to use the momentum of the 1964 Civil Rights Act to win federal protection for a voting rights statute. During January and February, 1965, King and SCLC led a series of demonstrations to the Dallas County Courthouse.

“Bloody Sunday” was televised around the world. Obama leads Selma 50th anniversary march. "We Shall Overcome": LBJ and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. “We Shall Overcome”: LBJ and the 1965 Voting Rights Act On March 15, just over a week after Bloody Sunday, Pres.

Lyndon B. Johnson introduced voting rights legislation in an address to a joint session of Congress. In what became a famous speech, he identified the clash in Selma as a turning point in U.S. history akin to the Battles of Lexington and Concord in the American Revolution. Invoking the protest song that had become the unofficial anthem of the American civil rights movement, Johnson said: Selma, 50 ans plus tard.