Quilling - Turning Paper Strips into Intricate Artworks

Quilling has been around for hundreds of years, but it’s still as impressive and popular now as it was during the Renaissance. The art of quilling first became popular during the Renaissance, when nuns and monks would use it to roll gold-gilded paper and decorate religious objects, as an alternative to the expensive gold filigree. Later, during the 18th and 19th centuries, it became a favorite pass-time of English ladies who created wonderful decorations for their furniture and candles, through quilling.

Bio

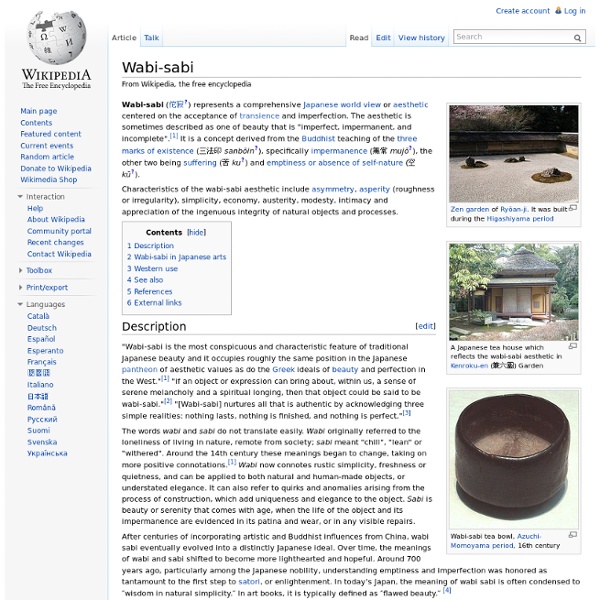

The first 300 words from Wabi-Sabi: for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers “Wabi-sabi is a beauty of things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. It is a beauty of things modest and humble. It is a beauty of things unconventional.” “The immediate catalyst for this book was a widely publicized tea event in Japan.

Defence in depth

Defence in depth (also known as deep or elastic defence) is a military strategy; it seeks to delay rather than prevent the advance of an attacker, buying time and causing additional casualties by yielding space. Rather than defeating an attacker with a single, strong defensive line, defence in depth relies on the tendency of an attack to lose momentum over a period of time or as it covers a larger area. A defender can thus yield lightly defended territory in an effort to stress an attacker's logistics or spread out a numerically superior attacking force. Once an attacker has lost momentum or is forced to spread out to pacify a large area, defensive counter-attacks can be mounted on the attacker's weak points with the goal being to cause attrition warfare or drive the attacker back to its original starting position. The idea of defence in depth is now widely used to describe multi-layered or redundant protections for non-military situations, both tactical and strategic. Examples[edit]

Everything but the Paper Cut: Eye-popping Ways Artists Use Paper

In the year since the Museum of Art and Design reopened in its new digs on Columbus Circle, they've been delivering consistently compelling shows--from punk-rock lace to radical knitting experiments. The newest, "Slash: Paper Under the Knife", opened last weekend and runs through April 4, 2010. The focus is paper--and the way contemporary artists have used paper itself as a medium, whether by cutting, tearing, burning, or shredding.

Military Revolution

Origin of the concept[edit] Roberts first proposed the concept of a military revolution in 1955. On 21 January of that year he delivered a lecture before the Queen's University of Belfast; later published as an article, The Military Revolution, 1560–1660, that has fueled debate in historical circles for five decades, in which the concept has been continually redefined and challenged. Though historians often challenge Roberts' theory, they usually agree with his basic proposal that European methods of warfare changed profoundly somewhere around or during the Early Modern Period.

page corner bookmarks

This project comes to you at the request of Twitterer @GCcapitalM. I used to believe that a person could never have too many books, or too many bookmarks. Then I moved into an apartment slightly larger than some people’s closets (and much smaller than many people’s garages) and all these beliefs got turned on their naïeve little heads. But what a person can always look for more of is really cool unique bookmarks. Placeholders special enough for the books that are special enough to remain in your culled-out-of-spacial-necessity collection.

Wabi Sabi

Wabi-Sabi: For Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers, by Leonard Koren ISBN 1880656124 This page is also referred to for the Wabisabi Wiki Wabi-sabi is the quintessential Japanese aesthetic. It is a beauty of things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. It is a beauty of things modest and humble. It is a beauty of things unconventional...

Culminating point

The culminating point in military strategy is the point at which a military force no longer is able to perform its operations. On the offensive, the culminating point marks the time when the attacking force can no longer continue its advance, because of supply problems, the opposing force, or the need for rest. The task of the attacker is to complete its objectives before the culminating point is reached. The task of the defender on the other hand, is to bring the attacking force to its culminating point before its objectives are completed.

Mountains of Books Become Mountains

I thought I’d seen every type of book carving imaginable, until I ran across these jaw dropping creations by Guy Laramee. His works are so sculptural, so movingly natural in their form, they’ve really touched me. His works are inspired by a fascination with so-called progress in society: a thinking which says the book is dead, libraries are obsolete and technology is the only way of the future. His thoughts: “One might say: so what? Do we really believe that “new technologies” will change anything concerning our existential dilemma, our human condition?