Fractal. Figure 1a.

The Mandelbrot set illustrates self-similarity. As the image is enlarged, the same pattern re-appears so that it is virtually impossible to determine the scale being examined. Figure 1b. The same fractal magnified six times. Figure 1c. Figure 1d. Fractals are distinguished from regular geometric figures by their fractal dimensional scaling. As mathematical equations, fractals are usually nowhere differentiable.[2][5][8] An infinite fractal curve can be conceived of as winding through space differently from an ordinary line, still being a 1-dimensional line yet having a fractal dimension indicating it also resembles a surface.[7]:48[2]:15 There is some disagreement amongst authorities about how the concept of a fractal should be formally defined. Introduction[edit] The word "fractal" often has different connotations for laypeople than mathematicians, where the layperson is more likely to be familiar with fractal art than a mathematical conception.

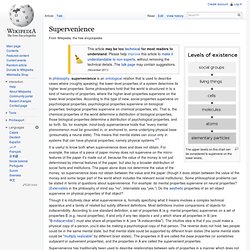

History[edit] Figure 2. Philosophy: General > Philosophy Map. Western Philosophy. Supervenience. The upper levels on this chart can be considered to supervene on the lower levels.

In philosophy, supervenience is an ontological relation that is used to describe cases where (roughly speaking) the lower-level properties of a system determine its higher level properties. Some philosophers hold that the world is structured in to a kind of hierarchy of properties, where the higher level properties supervene on the lower level properties. According to this type of view, social properties supervene on psychological properties, psychological properties supervene on biological properties, biological properties supervene on chemical properties, etc. Fideism. Fideism is an epistemological theory which maintains that faith is independent of reason, or that reason and faith are hostile to each other and faith is superior at arriving at particular truths (see natural theology).

The word fideism comes from fides, the Latin word for faith, and literally means "faith-ism. Philosophy. Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with reality, existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language.[1][2] Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational argument.[3] In more casual speech, by extension, "philosophy" can refer to "the most basic beliefs, concepts, and attitudes of an individual or group".[4] The word "philosophy" comes from the Ancient Greek φιλοσοφία (philosophia), which literally means "love of wisdom".[5][6][7] The introduction of the terms "philosopher" and "philosophy" has been ascribed to the Greek thinker Pythagoras.[8] Areas of inquiry Philosophy is divided into many sub-fields.

These include epistemology, logic, metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics.[9][10] Some of the major areas of study are considered individually below. Philosophy of logic. Following the developments in Formal logic with symbolic logic in the late nineteenth century and mathematical logic in the twentieth, topics traditionally treated by logic not being part of formal logic have tended to be termed either philosophy of logic or philosophical logic if no longer simply logic.

Compared to the history of logic the demarcation between philosophy of logic and philosophical logic is of recent coinage and not always entirely clear. Characterisations include This article outlines issues in philosophy of logic or provides links to relevant articles or both. Introduction[edit] Metaphysics. Metaphysics is a traditional branch of philosophy concerned with explaining the fundamental nature of being and the world that encompasses it,[1] although the term is not easily defined.[2] Traditionally, metaphysics attempts to answer two basic questions in the broadest possible terms:[3] Ultimately, what is there?

Meta-ontology. Meta-ontology is a term of recent origin first used by Peter van Inwagen in analyzing Willard Van Orman Quine's critique of Rudolf Carnap's metaphysics,[1] where Quine introduced a formal technique for determining the ontological commitments in a comparison of ontologies.[2] Thomas Hofweber, while acknowledging that the use of the term is controversial, suggests that, although strictly construed meta-ontology is a separate metatheory of ontology, the field of ontology can be more broadly construed as containing its metatheory.[3][4] Advocates of the term 'meta-ontology' seek to distinguish 'ontology' (which investigates what there is) from 'meta'-ontology (which investigates what we are asking when we ask what there is).[1][5][6] Amie L.

See also[edit] References[edit] ^ Jump up to: a b c Peter Van Inwagen (1998). Metacognition. Metacognition is defined as "cognition about cognition", or "knowing about knowing".

It comes from the root word "meta", meaning beyond.[1] It can take many forms; it includes knowledge about when and how to use particular strategies for learning or for problem solving.[1] There are generally two components of metacognition: knowledge about cognition, and regulation of cognition.[2] Metamemory, defined as knowing about memory and mnemonic strategies, is an especially important form of metacognition.[3] Differences in metacognitive processing across cultures have not been widely studied, but could provide better outcomes in cross-cultural learning between teachers and students.[4]

Ontology. Study of the nature of being, becoming, existence or reality, as well as the basic categories of being and their relations Parmenides was among the first to propose an ontological characterization of the fundamental nature of reality.

Etymology[edit] While the etymology is Greek, the oldest extant record of the word itself, the New Latin form ontologia, appeared in 1606 in the work Ogdoas Scholastica by Jacob Lorhard (Lorhardus) and in 1613 in the Lexicon philosophicum by Rudolf Göckel (Goclenius). The first occurrence in English of ontology as recorded by the OED (Oxford English Dictionary, online edition, 2008) came in a work by Gideon Harvey (1636/7–1702): Archelogia philosophica nova; or, New principles of Philosophy. Philosophical realism. Realists tend to believe that whatever we believe now is only an approximation of reality and that every new observation brings us closer to understanding reality.[2] In its Kantian sense, realism is contrasted with idealism.

In a contemporary sense, realism is contrasted with anti-realism, primarily in the philosophy of science. History[edit] Objectivity (philosophy) "Objectivism" is a term that describes a branch of philosophy that originated in the early nineteenth century. Gottlob Frege was the first to apply it, when he expounded an epistemological and metaphysical theory contrary to that of Immanuel Kant. Kant's rationalism attempted to reconcile the failures he perceived in philosophical realism. Epistemology. A branch of philosophy concerned with the nature and scope of knowledge Epistemology (; from Greek ἐπιστήμη, epistēmē, meaning 'knowledge', and -logy) is the branch of philosophy concerned with the theory of knowledge.

Epistemology is the study of the nature of knowledge, justification, and the rationality of belief. Much debate in epistemology centers on four areas: (1) the philosophical analysis of the nature of knowledge and how it relates to such concepts as truth, belief, and justification,[1][2] (2) various problems of skepticism, (3) the sources and scope of knowledge and justified belief, and (4) the criteria for knowledge and justification.

Epistemology addresses such questions as: "What makes justified beliefs justified? ",[3] "What does it mean to say that we know something? " 'Pataphysics. Jarry in Alfortville 'Pataphysics (French: 'pataphysique) is a philosophy or media theory dedicated to studying what lies beyond the realm of metaphysics. The concept was coined by French writer Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), who defined 'pataphysics as "the science of imaginary solutions, which symbolically attributes the properties of objects, described by their virtuality, to their lineaments".[1] Natural philosophy. A celestial map from the 17th century, by the Dutch cartographer Frederik De Wit Natural philosophy or the philosophy of nature (from Latin philosophia naturalis) was the philosophical study of nature and the physical universe that was dominant before the development of modern science.

It is considered to be the precursor of natural sciences such as physics. Natural science historically developed out of philosophy or, more specifically, natural philosophy. At older universities, long-established Chairs of Natural Philosophy are nowadays occupied mainly by physics professors. Philosophy of mind. A phrenological mapping[1] of the brain – phrenology was among the first attempts to correlate mental functions with specific parts of the brain Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that studies the nature of the mind, mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness, and their relationship to the physical body, particularly the brain. The mind–body problem, i.e. the relationship of the mind to the body, is commonly seen as one key issue in philosophy of mind, although there are other issues concerning the nature of the mind that do not involve its relation to the physical body, such as how consciousness is possible and the nature of particular mental states.[2][3][4] Mind–body problem[edit] Our perceptual experiences depend on stimuli that arrive at our various sensory organs from the external world, and these stimuli cause changes in our mental states, ultimately causing us to feel a sensation, which may be pleasant or unpleasant.

Arguments for dualism[edit] Skepticism. Skepticism or scepticism (see American and British English spelling differences) is generally any questioning attitude towards knowledge, facts, or opinions/beliefs stated as facts,[1] or doubt regarding claims that are taken for granted elsewhere.[2] Philosophy of science.

Fermat's Last Theorem. The 1670 edition of Diophantus' Arithmetica includes Fermat's commentary, particularly his "Last Theorem" (Observatio Domini Petri de Fermat). In number theory, Fermat's Last Theorem (sometimes called Fermat's conjecture, especially in older texts) states that no three positive integers a, b, and c can satisfy the equation an + bn = cn for any integer value of n greater than two. Computational irreducibility. Computational irreducibility is one of the main ideas proposed by Stephen Wolfram in his book A New Kind of Science. Reductionism. Descartes held that non-human animals could be reductively explained as automata — De homine, 1662. Gödel's incompleteness theorems.

Gödel's incompleteness theorems are two theorems of mathematical logic that establish inherent limitations of all but the most trivial axiomatic systems capable of doing arithmetic. Chaos theory. A double rod pendulum animation showing chaotic behavior. Starting the pendulum from a slightly different initial condition would result in a completely different trajectory. Computational complexity theory. Computational complexity theory is a branch of the theory of computation in theoretical computer science and mathematics that focuses on classifying computational problems according to their inherent difficulty, and relating those classes to each other. A computational problem is understood to be a task that is in principle amenable to being solved by a computer, which is equivalent to stating that the problem may be solved by mechanical application of mathematical steps, such as an algorithm.

A problem is regarded as inherently difficult if its solution requires significant resources, whatever the algorithm used. Uncertainty principle. Where ħ is the reduced Planck constant. The original heuristic argument that such a limit should exist was given by Heisenberg, after whom it is sometimes named the Heisenberg principle. A New Kind of Science. A New Kind of Science is a best-selling,[1] controversial book by Stephen Wolfram, published in 2002. It contains an empirical and systematic study of computational systems such as cellular automata. Philosophy of mathematics. List of set theory topics. Mereology. Lyapunov fractal. Rhetoric. Sophism. List of philosophers. Portal:Philosophy. Occasionalism. Neoplatonism and Gnosticism. Belief system. Anekantavada. Pluralism.

Fallibilism. Monism. Dualism. Holism. Determinism. Fatalism. Predeterminism. Causality. Reductionism. Emergentism. Functionalism. Idealism. Phenomenalism. Secular humanism. Nihilism. Moral nihilism. Non-cognitivism. Black comedy. Absurdism. Solipsism. Existentialism.

Atheism. Naturalism. Materialism. Structuralism. Post-structuralism. Physicalism. Relativism. Perspectivism. Agnosticism. Ignosticism. Compatibilism. Religion. Pantheism. Deism. State religion. Philosophy of religion. Positivism. Empiricism. Scientism. Semantic interoperability. Infinitism. Finitism. Ultrafinitism. Epicureanism. Temporal finitism. Psychological hedonism. Indeterminism. Uncertainty. Free will.