Philip K. Dick. Personal life[edit] The family moved to the San Francisco Bay Area.

When Philip turned five, his father was transferred to Reno, Nevada. When Dorothy refused to move, she and Joseph divorced. Both parents fought for custody of Philip, which was awarded to the mother. Dorothy, determined to raise Philip alone, took a job in Washington, D.C., and moved there with her son. From 1948 to 1952, Dick worked at Art Music Company, a record store on Telegraph Avenue. Dick was married five times: Jeanette Marlin (May to November 1948)Kleo Apostolides (June 14, 1950 to 1959)Anne Williams Rubinstein (April 1, 1959 to October 1965)Nancy Hackett (July 6, 1966 to 1972)Leslie (Tessa) Busby (April 18, 1973 to 1977) Dick had three children, Laura Archer (February 25, 1960), Isolde Freya (now Isa Dick Hackett) (March 15, 1967), and Christopher Kenneth (July 25, 1973). Career[edit] Paranormal experiences and mental health issues[edit] Pen names[edit] Style and works[edit] Themes[edit] —Steven Owen Godersky.

When Philip K. Dick turned to Christianity. Once considered a cult figure, the science fiction author Philip K.

Dick is now recognized as one of the most prescient and powerful writers of the 20th century. His work not only foreshadowed many of the technological anxieties and possibilities of our era, but shaped the sensibility of the sixties and seventies in ways that continue to mark us today. His tumultuous personal and psychic life not only fed his art, but led him to pursue a quirky mysticism that took a myriad of forms. In 1963 Dick turned to Christianity after a terrifying vision. By the fall of that year Dick’s third marriage had devolved along with the emotional stability of both partners; Dick even managed to have the psychiatrist he shared with his wife, Anne, briefly commit her to a mental hospital. Philip K. Dick and the Fake Humans. Image: NikiSublime We live in Philip K.

Dick’s future, not George Orwell’s or Aldous Huxley’s. This essay is featured in Global Dystopias. Order your copy here. This is not the dystopia we were promised. Dystopias tend toward fantasies of absolute control, in which the system sees all, knows all, and controls all. This does not look like totalitarianism unless you squint very hard indeed.

Standard utopias and standard dystopias are each perfect after their own particular fashion. Philip K. Dick’s Moral Vision. [Editor’s note: on this 34th anniversary of the death of Philip K.

Dick, I’m sharing the 10th and final chapter of Patricia S. Warrick’s bibliographical retrospective “Mind in Motion” (1987). It’s a good reminder of what makes PKD’s work so unique and enduringly relevant.] This critical study of Dick’s fiction is a work without a concluding chapter – and appropriately so. To summarize his ideas, to categorize his work, to deliver the final word would be to violate Dick’s vision. But if we cannot make a final statement, we can at least note the significance of his opus of fiction for the times in which we live. He had a remarkable sense of the cultural transformation taking place in the last half of the twentieth century. Dick’s fiction calls up our basic cultural assumptions, requires us to reexamine them, and points out the destructive destinations to which they are carrying us. Watch A Day in the Afterlife, a 1994 documentary about Philip K. Dick.

Amazon Debuts Philip K. Dick's 'The Man in the High Castle' Series by Ridley Scott. Hey Dick-Heads, are you excited for the The Man in the High Castle?

Amazon Studios has released a new teaser in advance of the debut of the first two series episodes at San Diego Comic Con on July 10th (if you can’t get to San Diego, EW is going to stream the event live): Based on Philip K. Dick’s award-winning novel, and executive produced by Ridley Scott (Blade Runner), The Man in the High Castle explores what it would be like if the Allied Powers had lost WWII, and Japan and Germany ruled the United States. Starring Rufus Sewell (John Adams), Luke Kleintank (Pretty Little Liars) and Alexa Davalos (Mob City), the series results from the Amazon Studios one hour pilot, which you can access here if you subscribe to Amazon Prime.

Dick set The Man in the High Castle in 1962, fifteen years after the end of a fictional longer Second World War (1939–47). For those hungry for more, Amazon Studios previously released some clips: Philip K. Dick Quotes (Author of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?) “Grief reunites you with what you've lost.

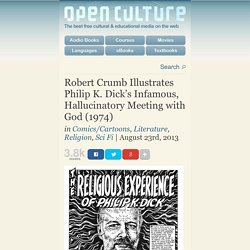

It's a merging; you go with the loved thing or person that's going away. You follow it a far as you can go. The Distorted Realities of Philip K. Dick. Robert Crumb Illustrates Philip K. Dick’s Infamous, Hallucinatory Meeting with God (1974) “I saw God,” Fat states, and Kevin and I and Sherri state, “No, you just saw something like God, exactly like God.”

And having spoke, we do not stay to hear the answer, like jesting Pilate, upon his asking, “What is truth?” –Philip K. Dick, VALIS In the months of February and March, 1974, Philip K. Dick met God, or something like God, or what he thought was God, at least, in a hallucinatory experience he chronicled in several obsessively dense diaries that recently saw publication as The Exegesis of Philip K. LSD-triggered psychotic break, genuine religious experience, or something else entirely, whatever Dick’s encounter meant, he didn’t let the opportunity to turn it into art slip by him, and neither did outsider cartoonist and PKD fan Robert Crumb. If you only know Crumb as the creator of lascivious Rubenesque women and schlubby, druggy horndog hipsters (like Fritz the Cat), you may be surprised by these emotionally realist illustrations.

Related Content: Philip K. Dick - The Man Who Remembered the Future. Did sci-fi author Philip K.

Dick see the future? Could he literally have been precognitive? This is one of the conclusions of a new biography by the consciousness theorist Anthony Peake. Philip K Dick - A Day in the Afterlife (1994)