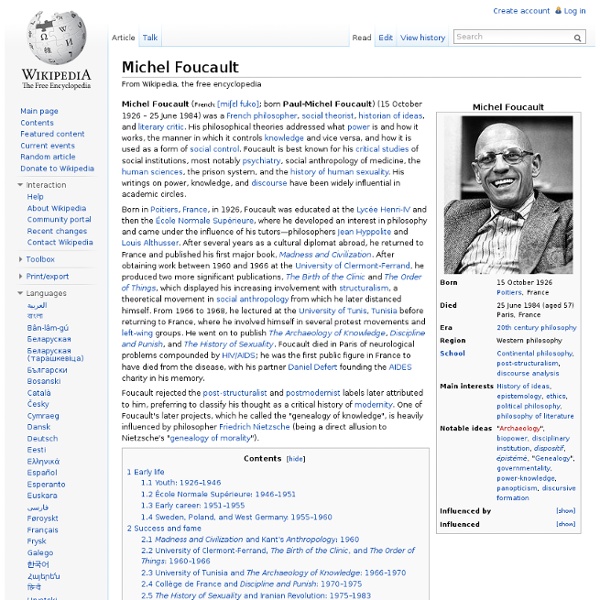

Michel Foucault

Foucault–Habermas debate

The debate was a dialogue between texts and followers; Foucault and Habermas did not actually debate in person, though they were considering a formal one in the U.S. before Foucault's death in 1984. Habermas' essay, Taking Aim at the Heart of the Present (1984) was altered before release in order to account for Foucault's inability to reply. Foucault discovers in Kant, as the first philosopher, an archer who aims his arrow at the heart of the most actual features of the present and so opens the discourse of modernity ... but Kant's philosophy of history, the speculation about a state of freedom, about world-citizenship and eternal peace, the interpretation of revolutionary enthusiasm as a sign of historical 'progress toward betterment' – must not each line provoke the scorn of Foucault, the theoretician of power? Has not history, under the stoic gaze of the archaeologist Foucault, frozen into an iceberg covered with the crystals of arbitrary formulations of discourse? See also[edit]

Biopower

"Biopower" is a term coined by French scholar, historian, and social theorist Michel Foucault. It relates to the practice of modern nation states and their regulation of their subjects through "an explosion of numerous and diverse techniques for achieving the subjugations of bodies and the control of populations".[1] Foucault first used the term in his lecture courses at the Collège de France,[2][3] but the term first appeared in print in The Will To Knowledge, Foucault's first volume of The History of Sexuality.[4] In Foucault's work, it has been used to refer to practices of public health, regulation of heredity, and risk regulation, among many other regulatory mechanisms often linked less directly with literal physical health. It is closely related to a term he uses much less frequently, but which subsequent thinkers have taken up independently, biopolitics. Foucault and the concept of biopower[edit] Pre-Foucault usage of 'biopolitics'[edit] Territory[edit]

Related:

Related: