Fake news (détecter...) Breaking News Consumer's Handbook: Fake News Edition. BROOKE GLADSTONE: Drawing a distinction between fake and real news is going to be hard for those Facebook and Google employees tasked with bird dogging offending sites, but it shouldn’t be so hard for you, the consumer.

Melissa Zimdars, professor of communication and media at Merrimack College, has made a list of more than a hundred problematic news sites, along with tips for sorting out the truthful from the troublesome. She got into the fake news sorting racket after a hot tip. MELISSA ZIMDARS: Someone alerted me to the fact that when you searched for the popular vote on Google, the first Google news item that came up was a fake news website saying that Hillary Clinton lost the popular vote. BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. MELISSA ZIMDARS: And that's when I was like, yeah, we need to teach our students [LAUGHS] how to navigate this. BROOKE GLADSTONE: Tell me what the reaction’s been to the doc? BROOKE GLADSTONE: So you’re getting trolled. MELISSA ZIMDARS: Majorly trolled, yes. How did the news go ‘fake’? When the media went social. The Collins Dictionary word of the year for 2017 is, disappointingly, “fake news”.

We say disappointingly, because the ubiquity of that phrase among journalists, academics and policymakers is partly why the debate around this issue is so simplistic. The phrase is grossly inadequate to explain the nature and scale of the problem. (Were those Russian ads displayed at the congressional hearings last week news, for example?) But what’s more troubling, and the reason that we simply cannot use the phrase any more, is that it is being used by politicians around the world as a weapon against the fourth estate and an excuse to censor free speech.

Definitions matter. Social media force us to live our lives in public, positioned centre-stage in our very own daily performances. The social networks are engineered so that we are constantly assessing others – and being assessed ourselves. We grudgingly accept these public performances when it comes to our travels, shopping, dating, and dining. Is This True? A Fake News Database — Politico. Cosa ha scoperto il New York Times sul rischio fake news in Italia. Fake news, l'imprenditore che gestisce 19 siti pro-Salvini e pro-M5S. Ultimo capitolo della caccia a siti che diffondono sistematicamente informazioni fuorvianti o vere e proprie bufale.

Il noto debunker David Puente sul suo blog ha pubblicato i risultati di una ricerca sulle pagine web pro-M5S e pro-Lega riconducibili a un imprenditore della provincia di Napoli. Marco Mignogna, di Afragola, gestisce ben 19 siti di propaganda grillina o leghista. Puente ha individuato collegamenti tra pagine Facebook, indirizzi di posta elettronica, pagine web e banner pubblicitari scoprendo che tutto il traffico generava introiti per un solo account Google Adsense.

L’amara verità sulle notizie false - Annamaria Testa. Fake News: A Library Resource Round-Up. Les fake news peuvent créer de faux souvenirs. Selon une étude publiée dans Psychological Science, les électeurs peuvent se créer de faux souvenirs après avoir été exposés à des informations inventées, en particulier si elles correspondent à leurs convictions politiques.

“Nul ne peut nier que les fake news sont un vrai problème”, commence Forbes. En se propageant via les réseaux sociaux, elles contribuent à renforcer des préjugés, influencent les gens et sont souvent difficiles à stopper. Elles conduiraient même à la fabrication de faux souvenirs, en particulier si ces fausses informations vont dans le sens de nos convictions.

C’est ce que montre une étude parue le 21 août dans la revue à comité de lecture Psychological Science. Il n’y a pas de démocratie possible sans vérité. “Notre époque est marquée par le recul sans précédent d’un des principaux héritages des Lumières : la vérité en tant que pilier moral et politique”, affirme la sociologue Eva Illouz dans ce long article publié par le quotidien israélien Ha’Aretz.

Elle y déplore le culte de la subjectivité et du relativisme, qui ont donné lieu à toutes les dérives de Trump ou de Nétanyahou, pour ne citer qu’eux. Si le mensonge est si répandu aujourd’hui dans l’espace public, c’est parce qu’il est désormais impuni et, plus inquiétant, parce qu’il semble souvent rapporter gros. The godfather of fake news. How fake news gets into our minds, and what you can do to resist it. Fake news leaves a lasting impression on the less smart.

By Alex Fradera One reason why fake news is dangerous is that we don’t like giving up reassuring certainties, and once we have a take on things, it colours further information – hence the seeming bulletproof nature of conspiracy theories and partisan political hatreds.

But new research in Intelligence suggests this is truer for some people than others. For mentally sharp people, the results suggest it’s relatively easy to jettison an outdated perspective, while for those of lower cognitive ability, the dregs remain. Jonas De keersmaecker and Arne Roets from the University of Ghent recruited 390 participants from an online pool, and asked them to read a description of a nurse named Nathalie. For some participants this description ended with a damning revelation: Nathalie had been stealing drugs from the hospital and selling them to buy designer clothes.

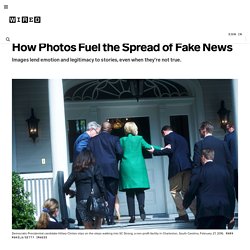

All participants then completed a short cognitive ability test, measuring their vocabulary knowledge of ten words. How Photos Fuel the Spread of Fake News. During a campaign stop in South Carolina last winter, Hillary Clinton stumbled as she climbed the steps of an antebellum mansion in Charleston.

Aides helped her regain her balance in a vulnerable but nondescript moment captured by Getty photographer Mark Makela. He didn’t think much of it until August, when the alt-right news site Breitbart touted it as evidence of Clinton’s failing health. “It was really bizarre and dispiriting to see,” he says. “We’re always attuned to photographic manipulation, but what was more sinister in this situation was the misappropriation of a photo.” Misappropriation and misrepresentation of images helped drive the growth of fake news.

Such stories rely on images to sell bogus narratives. This rise has been driven both by the preponderance of images available online, and the ease with which they can be manipulated. Photos play a key role in making fake news stories go viral by bolstering the emotional tenor of the lie. Go Back to Top. Introducing This Is Fake, Slate’s tool for stopping fake news on Facebook. One of the more extreme symptoms of media dysfunction in the past several months has been the ascendance of “fake news”—fabricated news stories that purport to be factual.

The phenomenon is not altogether novel, but the scale at which it is now being produced and consumed is unprecedented. A BuzzFeed data analysis found that viral stories falsely claiming that the Pope had endorsed Donald Trump, that Hillary Clinton was implicated in the murder of an FBI agent, that Clinton had sold weapons to ISIS, all received more Facebook engagement than the most popular news stories from established outlets such as the New York Times and CNN. Made-up stories with a liberal slant made the rounds as well, although the evidence suggests they propagated less widely.